This is an essay that I wrote in March 2007 for an independent study music class at Cornell. As Jamaican music continues to evolve, I’ll update this post to reflect new developments to the genre. Enjoy! (Last updated in 2007.)

Introduction

In surveying the development and contribution of various musical styles, perhaps nothing is as prominent in recent history as the musical creations that stem from the tiny Caribbean island of Jamaica. The senses come to life when visiting or surrounded by the mere concept of Jamaica, whether imagining Dunn’s River Falls, tasting ackee and salt fish, or smelling saltwater on the shores of Negril. Yet it can be argued that hearing what comes from Jamaica is the most appealing sense of them all: allowing the rhythmic uniqueness that is Jamaican music to become more than listening to it, allowing it to transform into a feeling. What is it, exactly, about Jamaican music that makes it stand out when lined up against the likes of R&B, salsa, or other forms of music from across the globe? Do these styles not have their own particular sound that makes them equally attractive to their lovers and listeners? Of course. Yet Jamaica possesses something deep down inside of the music, whether it’s a richly diverse bass line or the mingling of instruments that weave themselves in and out of sound.

Jamaican music, along with the extremely important contributions of the artists, musicians, producers and engineers, has a special combination of qualities: a spirit of the people, one that evolves with the population and culture over time and contributes to the diverse nature of the music, becoming deeply rooted in the essence of Jamaica. The social commentary, political upheaval, unique music styles of the entertainers, dancehall and sound system excitement: all of these things shape the mold of Jamaican music, but it is the composition of the music itself that makes it definitively Jamaican. Jamaican music is anything but predictable. It refuses to be static and for the few decades that the music has existed, it has continued to evolve into an even more structured and diverse sound, all the while remaining essentially Jamaican and upholding to past traditions even in the face of newer compositions. These things shape the sound of the music, and regardless of international popularity, the island never fails to keep the music inherently Jamaican.

The conception of early Jamaican music

From the abolition of slavery in Jamaica in 1838 came not only a long-awaited sense of independence and freedom, but also a well-ingrained concept of music and religion. Slaves were formerly taught to play European instruments, further encouraging their thirst for musical expression. This led to the merging of prior cultural influences with European styles of music. During a period known as the Great Revival when religious practices were flourishing, music of the Pocomania church, quadrille bands, Kumina and Jonkanoo all contributed to the early stages of Jamaican music. Revival Zion, as well, played a part in the development of the Jamaican sound, possessing what would soon become traditional inclusions of instruments and styles. Steve Barrow and Peter Dalton, in their book The Rough Guide to Reggae, characterize Revival Zion and Pocomania as a combination of “African and Christian religious elements, [involving] handclapping, foot-stamping and the use of the bass drum, side drum, cymbals and rattle” (Dalton 5). Count Ossie and his Nyabinghi drumming were also influential during this early period of musical development (Dalton 23). From these early forms of music, the groundwork for what would sprout into the buds of a uniquely Jamaican sound would soon emerge. The first of these sounds is mento.

Mento is a combination of African and European popular music and is similar in sound to the fun and upbeat calypso music of Trinidad, and its influence affected Jamaica tremendously. The terms mento and calypso became almost interchangeable. Mento is also often compared to the rumba music of the Caribbean. The music shares a similar arrangement of instruments with quadrille bands, making use of the banjo, maracas, hand drums, guitar, kalimba and rumba box, the last two being thumb pianos. Other commonly used instruments are the steel pan, fiddle, shaker, penny whistle, bongo and bamboo saxophone (Dalton 6).

By the 1950s, mento became one of the largest influences on the development of Jamaican music. Leon Jackson from All Music Guide calls mento “the ribald, witty first cousin of Jamaican reggae,” and further states:

Like reggae, mento is marked by a shuffling, syncopated guitar strum, an irreverent attitude, and a lazy, swaying danceability. Unlike reggae, mento has no sacramental roots, nor does it strain after profundity. Instead, mento makes a religion of sexual braggadocio, drinking, and good times.

The traditional mento song “Touch Me Tomato” is a good demonstration of this genre of music. It fits Jackson’s definition of mento because it has a lazy and slightly upbeat rocking mood, with the guitar and drums as the lead instruments. It also features emphasis on the one, three, and four counts in the bass line. The lyrics are also fun and catchy, which is common in mento, where the lead singer exclaims, “Please mister don’t you touch me tomato, please don’t touch me tomato. Touch me and me pumpkin, potato; [but] me say don’t touch me tomato. Touch me this, touch me that; touch me everything I’ve got. Touch me plum and the apples too, but here’s one thing you must not do!” The lyrics suggest sexual innuendo as well, which is, as previously stated, another trait of mento and other soon to emerge genres on the island. In addition, it is important to note that the influence of mento carried on throughout the decades. This song was rerecorded by other artists years after the original. For example, The Jolly Boys, who Jackson calls “the foremost performers of mento,” recorded the song (CD 1, Track 2) in 1972 during a period when both ska and rocksteady had already experienced their period of popularity.

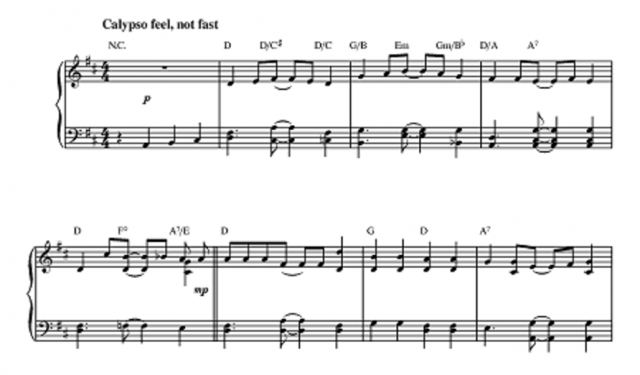

Another good example of a nice mento track is Lord Messam and The Calypsonians’ “Linstead Market” (CD 1, Track 1), whose composition is shown below:

“Linstead Market” (Music Notes)

The song is a smooth upbeat mento song with an easygoing feel to it. It is characterized by a flute segment as well as horns and drumming. As demonstrated in the bass line, emphasis is placed on counts one, three, and four, which is a widely used bass line construction that is found in a lot of mento songs, along with a strong emphasis on the last beat of each bar.

In these ways, mento has been a very important part of the development of reggae music. As the first definitive Jamaican genre of popular music, mento is especially significant because it is also the island’s first recorded music with the arrival of the Ken Khouri’s Federal Records in 1954 (Dalton 18). This would encourage record and music development on the island from the 1950s onward. From mento’s fast, upbeat sound emerged the genre that would quickly take over the island: ska.

The birth of Jamaica’s own sound

Mento soon became influenced by the R&B and New Orleans style jazz era that was taking place in the United States. This fusion of different genres of music birthed the creation of ska, a very fast, upbeat variation of mento that would become Jamaica’s first indigenous popular music, a sound inherently Jamaican in style. The love themes and singing style that was a result of R&B’s influence definitely inspired the lyrical sound of the music, but the production of the music itself is what made ska such a success. Instruments used include the saxophone, trombone, trumpets, drums, bass, pianos, guitars. The drums emphasize the second and fourth beats of each measure—the “backbeat” that was influenced by American R&B—while the horns and bass line reinforce the main pulse of the music. The upbeat, which emphasizes every other eighth note of each measure starting with the second eighth note, is highlighted by the guitar and saxophone, particularly during verses of the song. Musicians such as Don Drummond, Lloyd Knibbs, and Aubrey Adams would contribute their outstanding skills to the popular sound of ska. A good example of a ska song is Bob Marley and the Wailers’ 1963 song “Simmer Down” (CD 1, Track 3). The horn segment is very pronounced and the song is a great example of an upbeat, party-feel track. Other influential ska bands include The Skatalites, Desmond Dekker and the Aces (CD 1, Track 4) and Toots & The Maytals (CD 1, Tracks 5 & 6).

A good example of a slower production of ska is The Ethiopians’ song “Train to Skaville” (CD 1, Track 7):

“Train to Skaville” (Hal Leonard 216)

The song, although slower than the typical ska song, has the same basic construction and serves as a good example of the rocksteady and reggae eras soon to come. This track, which has the same rhythmic construction as Toots and the Maytals’ “5446, That’s My Number” (CD 1, Track 6), has a simple yet effective bass line. It is a good representation of the bridge between ska and the soon-to-emerge rocksteady style of the 1960s. This method of having more than one song on the same rhythm—or “riddim” as it is typically called in the Caribbean—would become one of the most popular and definitely Jamaican traits. This led to the naming of riddims over the years, with many of the early riddims getting their name from the first song cut on the riddim, such as in this case with the riddim name 5446, also commonly called the Boops riddim.

The 1960s saw ska in musical domination in Jamaica. Sound systems started to emerge, where they competed to play the latest R&B songs from abroad. Yet when these songs became harder to access, local artists began recording their own music on this new rhythmic music that became ska. Two of Jamaica’s most popular and productive producers, Clement ‘Coxsone’ Dodd and Duke Reid, started working with local bands to produce what would become some of the island’s best music. Prince Buster, Leslie Kong, Lee “Scratch” Perry and others would also prove influential during this time and onward. Dodd’s Studio One Records and Reid’s Treasure Isle Records would become two of the most powerful musical forces in the industry for decades thereafter, soon leading the music to rocksteady.

In the middle of the 1960s, some Jamaicans found themselves wanting a new change from the fast ska songs (Dalton 56). Independence had just been granted to the island on August 6th, 1962, and many people from the country parts of the island moved to the city for better job opportunities and a greater chance of success. Rudeboys became the nickname given to the youths who struggled to find this ideal place in the new lifestyle they encountered in the city. They became representatives of a slower style of music. Because of this, there was large influence on the desire for a different sound in the music and soon rocksteady would be the genre to fulfill this desire. A slower tempo, rocksteady reflected the soul of the people, with smooth ballads, rich bass lines, and beautiful instrumentation. The instruments worked in sound harmony, with the strings of a guitar playing in unison with the bass. It was during this time, as well, that the American R&B sound started slowing down to the smooth and slow sounds of Motown Records, a change that similarly reflects the shift in music in Jamaica. The one drop, which emphasizes the afterbeat (counts 2 and 4 of every measure), was also introduced in rocksteady, and although it could be thought of as doubled-up in ska, the one drop became more pronounced in rocksteady and, later, in reggae. Dalton states,

Rocksteady was slower, more refined and, most of all, cooler. Firstly, the regularly paced ‘walking’ basslines that ska inherited from r&b became much more broken-up: in rocksteady the bass didn’t play on every beat with equal emphasis, but rather played a repeated pattern that syncopated the rhythm. In turn, the bass and drums became much more prominent, with the horns taking on a supportive rather than a lead role (Dalton 55).

These traits helped rocksteady become revolutionary in its own sense, with the demand for more music increasing steadily.

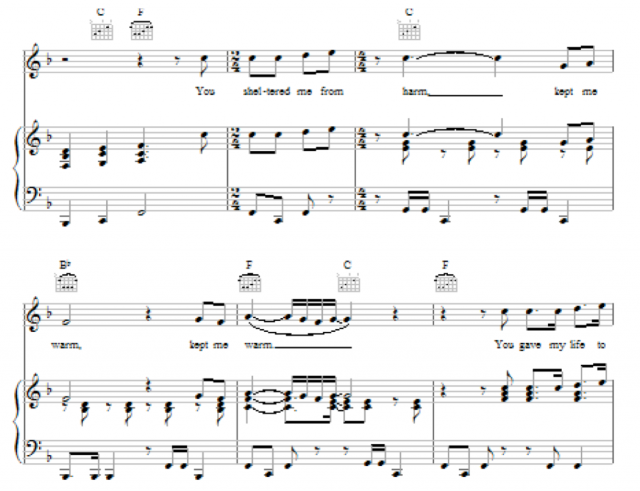

Dodd and Reid would find themselves competing for years, creating a musical war to see who could produce the best music with the best artists. Dodd, for example, produced the song “Simmer Down,” whereas Reid produced The Jamaicans’ hit song “Ba Ba Boom” (CD 1, Track 8). A good example of a rocksteady song is Ken Boothe’s “Everything I Own” (CD 1, Track 9). Below is the music for the song, which shows a smooth and simple bass line.

“Everything I Own” (Hal Leonard 60)

Another example is The Mighty Diamonds’ song “I Need a Roof” (CD 1, Track 10):

“I Need a Roof” (Hal Leonard 98)

This song has a more detailed bass line. The one drop can be seen in the treble line, in the enclosed red areas as shown. Artists that flourished during the rocksteady era include Jacob Miller, Derrick Harriott, Delroy Wilson, Alton Ellis, and Ken Boothe. Phyllis Dillon, another artist from this time, also sang over the song “Touch Me Tomato, her version being a rocksteady cut of the tune (CD 1, Track 11). This became a popular thing to do, many Jamaican artists remaking a popular song even if the genre was completely different yet still essentially Jamaican.

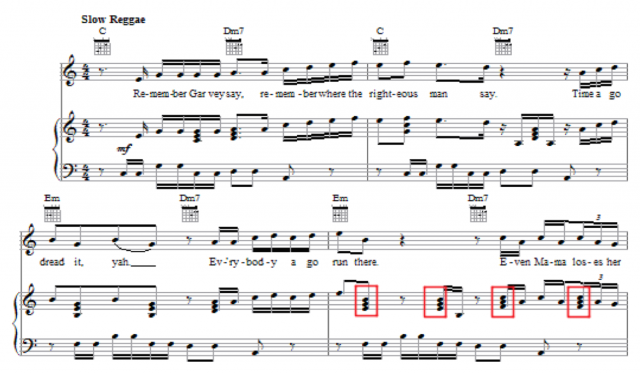

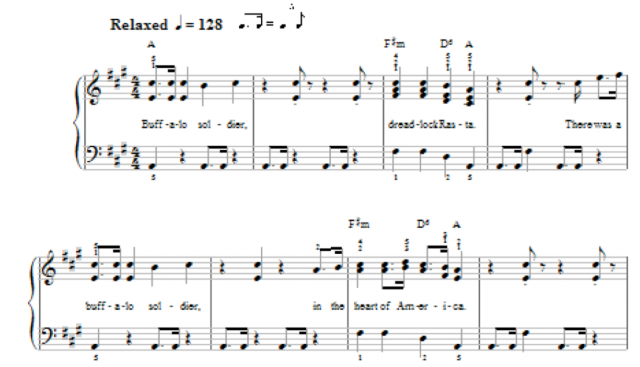

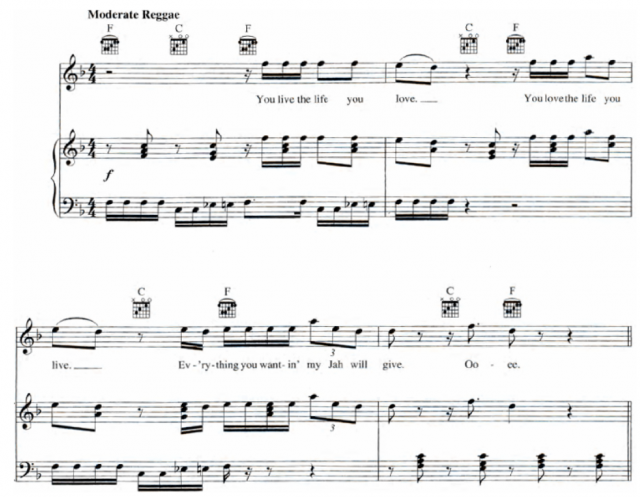

From the late 60s and throughout the 70s, social-political themes started becoming prominent in the music. Rastafarian culture started to rear its head in the world of Jamaican music, with the influences of Burning Spear and Bob Marley picking up momentum. Burning Spear’s 1975 song “Marcus Garvey” (CD 1, Track 12), for example, is a good example of a roots song that represents the essence of what would become known as roots reggae music. Roots reggae would include both characteristics of ska and rocksteady, as seen in Bob Marley’s 1970 “Mr. Brown” (CD 1, Track 13). From the roots style emerged the all-inclusive reggae that would cover different sounds and themes. Toots and the Maytals’ “Do the Reggay” (CD 1, Track 14) would be one of the first songs of the era as well as one of the first to call the genre by its name. Eric Donaldson’s “Cherry Oh baby” (CD 1, Track 15), Dennis Brown’s “Money In My Pocket” (CD Track 16), Bob Marley’s “No, Woman No Cry” (CD 1, Track 17), The Abyssinians’ “Satta Massagana” (CD 1, Track 18), and Jimmy Cliff’s “Vietnam” (CD 1, Track 19) are also other good examples of early reggae. Bob Marley’s “Buffalo Soldier” (CD 1, Track 20), with lead sheet music shown below, is another reggae song that features a staccato one-drop that would become popular in the sound of reggae. Both Bob Marley and Jimmy Cliff revolutionized the way the globe viewed reggae music, spreading its appreciation far beyond the shores of the island. Jimmy Cliff and his role in the movie “The Harder They Come” had a huge impact on this spreading of Jamaican music to other parts of the world. It was this film that would have a huge impact on the way the world viewed, understood, and interpreted Jamaican music for years to come. Nevertheless, Jamaica never shortchanged or altered the sound of its music, even though the world was beginning to pay more attention to the creativity stemming from the island. Groups from England such as Third World also encouraged the popularity of reggae.

“Buffalo Soldier” (Hal Leonard 8)

It was during this time that the versioning of named riddims became even more popular. Artists began cutting tracks on the same riddim around the same time, eventually leading to the production and sale of riddim albums. Riddims such as Real Rock (first produced in 1967 by Dodd) (CD 2, Tracks 1- 4), Heavenless (whose music is shown below) (CD 2, Tracks 5 & 6), and Stalag (CD 2, Tracks 7 & 8) became some of the most redone song elements of all reggae history, with some songs cut on these foundation riddims up to this very day. Real Rock and Heavenless, for example, according to an online database of over 50,000 songs at Riddimbase.net, both have over 300 different songs using these signature riddims. This shows how traditional even Jamaican popular music can be and how common it is to stick to the roots of the music even as time progresses.

“Greetings” (Hal Leonard 86)

It was also during this time that dub became popular. Dub is basically the instrumental of a song with the vocals stripped off, which creates the different versions, or instrumental riddims, of a song, sometimes enhanced by sound effects and echoing. U-Roy became notorious for his classic deejaying style. He inspired many to create a form of toasting, where deejays speak over a dub with clever things to say, that would grow into the DJ styles of the 80s, 90s and today. Dub instrumentals encouraged artists to perform in a different kind of way, allowing them to speak over the song in the same manner that one would toast a song by chatting on the microphone. The dub instrumental also caused excitement over what became known as dub reggae, where echoes, sound effects, and the fading in and out of the vocals on a track became popular. An example of this is U Roy’s “Crashie Sweep” (CD 2, Track 9), which is actually on the same riddim as The Mighty Diamonds’ “I Need a Roof.” Augustus Pablo, dub instrumentalist, also was influential during this period. King Tubby and Prince Jammy are two other important dub producers. Pablo, Lee Perry & King Tubby all came together and produced a superb dub track called “Splash Out Dub” (CD 2, Track 10). Putting the version of a song on the B side of the vinyl record became very popular. Dalton states that “the majority of reggae singles from 1973 onwards have had dub versions on their flips” (Dalton 447). Carolyn Cooper, author of the novel Sound Clash: Jamaican Dancehall Culture at Large, states:

The fact that the riddim is often identical for several DJ tunes confirms the potency of the beat in shaping dancehall aesthetics. The riddim itself becomes a compelling signifier, dubbing several times over the language form and message created by the DJ (Cooper 297-298).

This trend makes Jamaican music drastically different from any other genre in the world.

Dub also played another important role. As more and more Jamaican music was being produced, sound systems would have to find unique ways to entertain and win the crowd. The most popular way to do this was to have a special remake of a song, one that featured the sound system’s name in the track. These customized remakes, called dubplates, usually had funny and instigating lyrics that would lyrically attempt to destroy the credibility and popularity of other sound systems, which is a popular feature of sound clashes between different systems. This is when having multiple versions of a song became a phenomenon. Records started being produced with a song on the A side and the instrumental, or riddim version, on the B side. This encouraged the production of exclusive sound system remakes and would eventually lead to the popularity of dub reggae. An example of a specially made song for a sound system is Dawn Penn’s 1992 reggae song, “You Don’t Love Me” (CD 2, Track 11). In the original song, she croons: “No no no no, you don’t love me and I know now…’Cause you left me, baby, and I’ve got no place to go now. No no no no, I’ll do anything you say, boy.” Yet the special of the song (CD 2, Track 12), made for the popular sound system Saxon in the 90s, goes as follows: “No no no no, can’t test Saxon and you know now…‘Cause if you draw card, sound boy, it’s the last time you will play, boy. No no no no, Saxon plays any dub you play, boy…’Cause if you test him, sound boy, you have to pack up and run away boy.”

Growth of a new style

Reggae music was definitely in its prime but was soon to be challenged by a new flavor of Jamaican music. The popular roots themes from the likes of Burning Spear, Bob Marley and others started to decline after the death of Marley in 1981, whose musical influence, had it not existed, would have hindered the development of future Jamaican music altogether (White 340). The younger generations also started craving a new sense of expression in their music, and with versioning on riddims becoming so popular, the rise of DJs soon emerged. Thus arrived the creation of digital reggae, which became known as ragga. Starting in the early 80s, this new style of music became popular in its own right with a large number of new artists on the rise. Barrington Levy, Yellowman, and Eek-a-mouse were a few of the dozens of artists who were making a name for themselves in this decade. Songs such as Yellowman’s 1981 song “Zunguzung” (CD 2, Track 13) on the Diseases riddim and Dennis Brown’s 1983 hit song “Revolution” (CD 2, Track 14) on the Intercom riddim are a couple of the songs that were precursors to what became fully digitally produced tracks. One of the most popular songs of the digital ragga stage was Wayne Smith’s King Jammy-produced song “Under Me Sleng Teng” (CD 2, Track 15) in 1985, a song that would be known for years to pinpoint the start of ragga. The sound was fresh, different, and innovative. Although straying from the instrumental inclusion that reggae features, ragga was a new spin on the sound of Jamaica music, and one that would remain popular over the years.

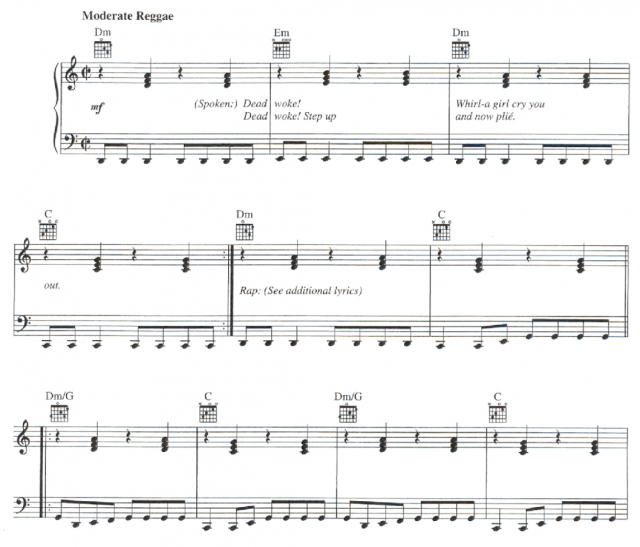

Artists such as Beenie Man, Shabba Ranks, and Super Cat emerged as dominating artists. Some of the most popular riddims of the 90s include Pepper Seed (CD 2, Track 16) and Joyride (CD 2, Track 17). Shabba Ranks’ song “Wicked Inna Bed” (CD 2, Track 18), released in 1989, is another good example of ragga in its early stages. It has a clear, heavy bass line, as indicated in the following:

“Wicked Inna Bed” (Hal Leonard 246)

Ragga, although digital in nature, also included traditional themes as well. The Kette Drum (CD 2, Track 19) riddim features Nyabinghi drumming that was popular around the time that music began developing itself on the island. It also knew how to slow itself down, with tracks such as Shabba Ranks’ “Flex” (CD 2, Track 20) (which actually sampled the bass line of the R&B group The Temptations’ song “Just My Imagination”) becoming popular internationally (Dalton 450). Ragga took over the island quickly, yet reggae was still large in its own right, with artists such as Garnett Silk (CD 3, Track 1), Cocoa Tea, Singing Melody (CD 3, Track 2), Beres Hammond and Marcia Griffiths (the last two being featured on the track “If You See Me Crying” (CD 3, Track 3)) dominating the industry and sometimes even crossing over to ragga riddims.

In the early to mid-90s, ragga began to change. The DJs were much more competitive, the lyrics were more sexually explicit and the audience was mainly the younger generation in Kingston and other urban areas. Hypnotic, sensual, waist-winding bass lines, feet-tapping rhythms, adrenaline-pumping tempos, and bold and sometimes disturbing lyrics all tie into one gigantic knot of music known as dancehall. It is music that encourages entertainment, enjoyment, and pleasure because of its spontaneity and variety. “Somewhere between 3000 and 5000 [dancehall] singles are produced every year” (Thompson 87). The genre started not so much as a separation from the previous forms of reggae but rather as a new interpretation of them. Dancehall became the “good time dance music” that the youth wanted so badly to hear (White 341). It soon became evident that dancehall was going to be more than just a temporary means of satisfaction. “The future of reggae [is] up to Jamaica’s youth;” thus if the youth want dancehall, then dancehall continues to flourish (White 341).

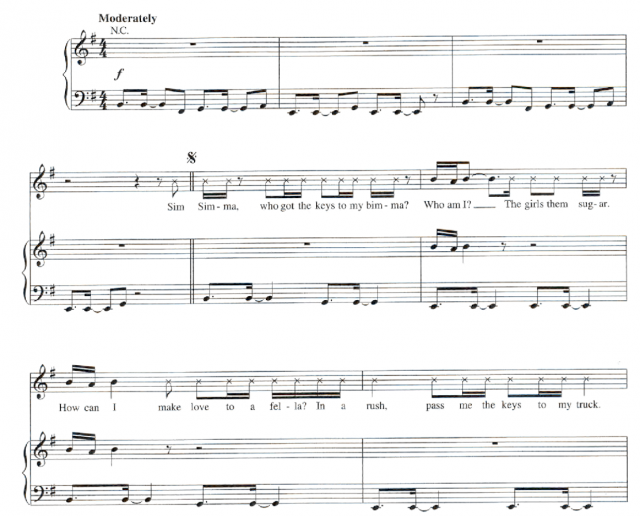

Riddim albums also became popular, which increased competition among artists to fight for the most popular track on a riddim. “Greensleeves” and “Riddim Driven” albums are a couple of the most popular compilations that release new riddims on a regular basis. Beenie Man’s song “Who Am I” (CD 3, Track 4), released in 1998 and eventually went on to become an international hit, is a good early dancehall selection:

“Who Am I” (Hal Leonard 238)

Producers such as Steely and Cleevie and Dave Kelly became some of the largest names in the production industry in Jamaica. By the end of the 90s and into the new millennium, the sound of dancehall progressed greatly. Bobby “Digital” Dixon and Stephen McGregor, son of the popular reggae artist Freddie McGregor, have become a production powerhouse in the past few years, with hit riddims like Power Cut (CD 3, Track 15). The sound of riddims changes drastically year to year, each a bit different and with a unique spin on what dancehall should sound like for a particular year. Riddims like Filthy (CD 3, Track 5) in 1998, Bug (CD 3, Track 6) in 1999, The Buzz (CD 3, Track 7) in 2001, Jonkanoo (CD 3, Track 8) in 2005, and Cashly (CD 3, Track 9) in 2006 show this variety in dancehall style. The Jonkanoo riddim, produced by Donovan “Vendetta” Bennett, was a success, the riddim getting its name from the early music form. Interesting to note is that a huge song on the riddim, Vybz Kartel’s “I Never” (CD 3, Track 8), actually is influenced by the chorus of Toots and the Maytals’ song “Never Grow Old” (CD 1, Track 5). Socially conscious themes remained relevant such as Bounty Killer’s son “Look” on the Bug riddim (CD 3, Track 6). Also popular were the typical themes of sex, weed, and general warring between artists to see who was better. Dancing tunes have been highly successful, especially after the influence of Elephant Man who is notorious for making dancing songs like 2004’s “Dance Di Chaka” (CD 3, Track 10) (which actually sounds like it has Pocomania and earlier music influences). Other popular songs include Ding Dong’s “Badman Forward, Badman Pull Up” (CD 3, Track 11) in 2005 (popular amongst the men) and Tony Matterhorn’s “Dutty Wine” (CD 3, Track 12) in 2006 (exclusively for the women). In these ways, dancehall became a popular music form in Jamaica yet is not the only genre on the island. Roots reggae also plays its part.

Culture, which is essentially like roots reggae of the 70s, began to surface in the late 90s right into the new millennium. Riddims such as Drop Leaf (CD 3, Track 13) and Seasons (CD 3, Track 14) (both of which became huge one drop songs in 2004) with artists such as Sizzla and the newly reformed Capelton and Buju Banton become just as popular as dancehall tunes. Through culture music and lovers’ rock, which is essentially a derivative of roots reggae that focuses mostly on love, reggae has continued to be a dominant force alongside the upbeat, digitally influenced dancehall. These styles possess the moderate tempo and one-drop theme of reggae music.

Conclusion

Over the past few decades, from mento all the way up to current dancehall vibes (CD 3, Tracks 15-20), Jamaican music has continued to evolve as evidenced by significant changes in the lead instruments, rhythmic development, and singing/DJing styles. Music itself may very well be the heart of Jamaica, and it is the creative drive of the artists, producers, musicians and engineers that provide the pulse that sustain it. In 2004, Dalton stated,

The island has produced some 100,000 records over the last 45 years – an extraordinary output for a population of little more than two million. Although few of these recordings have crossed over to audiences beyond the Jamaican community, it’s hard to think of any genre of popular music that has had a greater influence in the past couple of decades (Dalton X).

No matter what the genre, Jamaican music has continued to prove itself with unique, creative sounds worthy of praise. No matter what the year or riddim, the music remains a unique combination of innovation and creativity. The island is notorious for producing massive amounts of music each year, and the creativity never seems to stop. It is not simply the hit singles that make an impact, but also the persistency of the artists, many of them releasing music for years on end. Although the rest of the world forms its own opinion about Jamaican music, Jamaica makes it very clear that the music is not defined by outside views. Despite reggae’s internationalization, the music is a localized sound that remains rooted in the souls of the Jamaican people. Where will the music head in the future? It’s hard to tell, yet based on the way things are going, one can expect nothing short of excellence.

Works Cited

- Barrow, Steve. The Story of Jamaican Music. United Kingdom: Island Records, 2004.

- Barrow, Steve, and Peter Dalton. The Rough Guide to Reggae. 3rd ed. London: Penguin Books Ltd., 2004.

- Cooper, Carolyn. Sound Clash: Jamaican Dancehall Culture at Large. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2004.

- Hal Leonard Corporation. Ultimate Reggae: 42 of the Best. Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corporation, 2005.

- Jackson, Leon. The Jolly Boys. All Music Guide. 19 March 2007. <http://www.artistdirect.com/nad/music/artist/bio/0,,450142,00.html#bio>.

- Music Notes: Linstead market. 20 March 2007. <http://www.musicnotes.com/sheetmusic/scorch.asp?ppn=SC0010206>.

- Riddimbase. 23 March 2007. <http://riddimbase.net/statistics.php#> (site no longer available).

- Stolzoff, Norman. Wake the Town and Tell the People: Dancehall Culture in Jamaica. Durham: Duke University Press, 2000.

- Thompson, Dave. Reggae and Caribbean Music. San Francisco: Backbeat Books, 2002.

- White, Timothy. Catch a Fire: The Life of Bob Marley. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2000.

Playlist

CD 1

- Lord Messam & The Calypsonians – “Linstead Market”

- The Jolly Boys – “Touch Me Tomato”

- Bob Marley & The Wailers – “Simmer Down”

- Desmond Dekker & The Aces – “007 Shanty Town”

- Toots & The Maytals – “Never Grow Old”

- Toots & The Maytals – “5446, That’s My Number”

- The Ethiopians – “Train To Skaville”

- The Jamaicans – “Ba Ba Boom”

- Ken Boothe – “Everything I Own”

- The Mighty Diamonds – “I Need a Roof”

- Phyllis Dillon – “Touch Me Tomato”

- Burning Spear – “Marcus Garvey”

- Bob Marley & The Wailers – “Mr. Brown”

- Toots & The Maytals – “Do The Reggay”

- Eric Donaldson – “Cherry Oh Baby”

- Dennis Brown and U Roy – “Money In My Pocket”

- Bob Marley & The Wailers – “No Woman No Cry” (Remix)

- The Abyssinians – “Satta Massagana”

- Jimmy Cliff – “Vietnam”

- Bob Marley – “Buffalo Soldier”

CD 2

- Studio One – “Real Rock” (Real Rock Riddim)

- Cocoa Tea – “She Loves Me Now” (Real Rock Riddim)

- Dennis Brown – “Stop the Fussing and Fighting” (Real Rock Riddim)

- Cornell Campbell – “Rope In” (Real Rock Riddim)

- Half Pint – “Greetings” (Heavenless Riddim)

- Super Cat – “Under Pressure” (Heavenless Riddim)

- Tenor Saw – “Ring the Alarm” (Stalag Riddim)

- Sister Nancy – “Bam Bam” (Stalag Riddim)

- U Roy – “Crashie Sweep” (I Need a Roof Riddim)

- Augustus Pablo, Lee Perry & King Tubby – “Splash Out Dub”

- Dawn Penn – “You Don’t Love Me”

- Dawn Penn – “No, No, No, No” (Saxon Dubplate)

- Yellowman – “Zunguzung”

- Dennis Brown – “Revolution”

- Wayne Smith – “Under Me Sleng Teng”

- Spragga Benz – “Things a Gwan” (Pepper Seed Riddim)

- Wayne Wonder & Baby Cham – “Joyride” (Joyride Riddim)

- Shabba Ranks – “Wicked Inna Bed”

- Beenie Man – “Kette Drum” (Kette Drum Riddim)

- Shabba Ranks – “Flex”

CD 3

- Garnett Silk – “Oh Me, Oh My”

- Singing Melody – “Say What”

- Beres Hammond & Marcia Griffiths – “If You See Me Crying”

- Beenie Man – “Who Am I?”

- General Degree – “Traffic Blocking” (Filthy Riddim)

- Bounty Killer – “Look” (Bug Riddim)

- Mad Cobra – “Press Tiger” (The Buzz Riddim)

- Vybz Kartel – “I Never (Jonkanoo Riddim)

- Buju Banton – “Try Off A Yu” (Cashly Riddim)

- Elephant Man – “Dance Di Chaka”

- Ding Dong –“Badman Forward, Badman Pull Up”

- Tony Matterhorn – “Dutty Wine”

- Jah Cure – “Longing For” (Drop Leaf Riddim)

- Wayne Wonder – “I Still Believe” (Seasons Riddim)

- Sean Paul – “Get It Right” (Power Cut Riddim)

- Vybz Kartel and Nuclear – “Sipping Sizzurp” (Sizzurp Riddim)

- Buju Banton – “Crazy Talk” (Bad Dog Riddim)

- Future Fambo – “Nuh Dress Like Man” (Drop Draws Riddim)

- Movado – “Dreaming” (Dreaming Riddim)

- Shaggy – “Church Heathen” (Church Heathen Riddim)

Last updated: 2007

hi there! I’m not sure but I’m intrigued by the challenge! I’ll let you know if I find anything :)

I heard the best instrumental version of ” Greensleeves” on flute on a reggae radio station a few years ago and can’t remember who it was. I even called up the DJ and he couldn’t remember either.I suppose it might be ska or mento and not reggae but it was beautiful. When I Google reggae or ska Greensleeves, of course all that comes up is the record label Greensleeves (lol) Who would that’ve been. Any clue? Thanks

Excellent breakdown of the evolution of reggae and analysis of Jamaican music theory. The only addition I would make would be a reference the Alpha Boys School in Jamaica. Thank you.